This is the second part of a blog about the things I have been privileged to learn and experience, as a teacher in Prince George, about a culture that is alive, vibrant and being celebrated in school.

Part one of this blog can be found here.

Land Acknowledgement

We respectfully acknowledge the unceded ancestral lands of the Lheidli T’enneh, on whose land we live, work and play.

Lheidli T’enneh hubeh keyoh whuts’odelhti. Nts’ezla hubeh yun ts’uwhut’i, ts’uzt’en ink’ez ts’unuwhulyeh.

A few facts

- Prince George is on the unceded ancestral home of the Lheidli T’enneh, a sub-group of the Dakelh who are the indigenous people of a large area of British Columbia.

- Around 30% of the students in School District 57 – 3,651 pupils – are First Nation.

- British Columbia’s curriculum was recently redesigned to integrate Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into all subjects, at all grades levels (year groups).

The Dakelh language in school

As a substitute teacher I have visited lots of different schools in Prince George and in the majority of them students were regularly being exposed to Dakelh words.

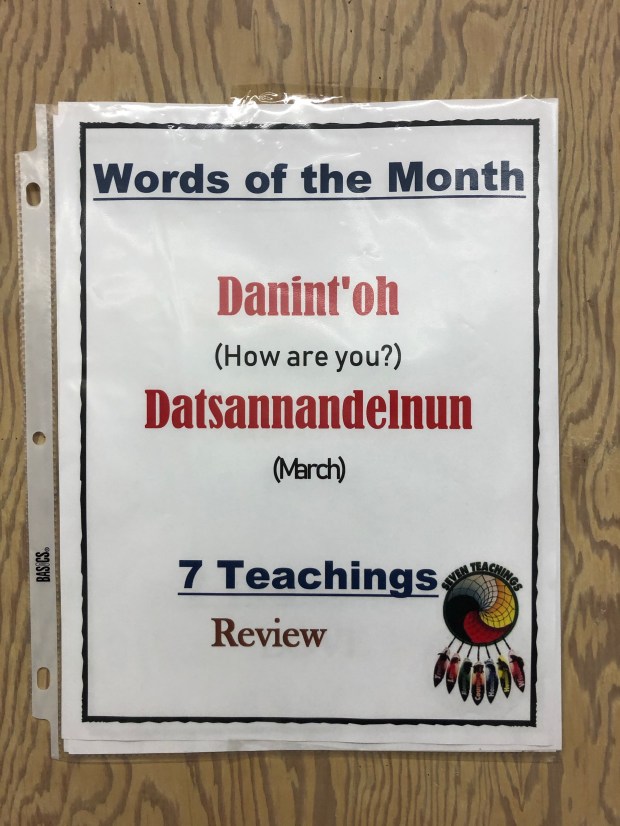

In some schools ‘Hadih’ (hello) was the greeting of choice during the morning announcement, in others there were posters showing which words the school was focusing on learning at that time and in one recently built school every sign was written in both languages.

As I mentioned in part one, throughout May 2021 I was working at a school where the principle would tell us the date in English and Dakelh each morning during the announcement. For days the Dakelh words ‘Dugoos Nandel Nun’, which means ‘the time of Sucker Fish Run’ or ‘May’ were struck in my head, like a track on repeat.

The beauty of hearing these words every single day in May, or should I say during the Dugoos Nandel Nun (the time of the Sucker Fish Run), meant that they were brought to life as real words which I’m confident I, and my class, will never forget how to say.

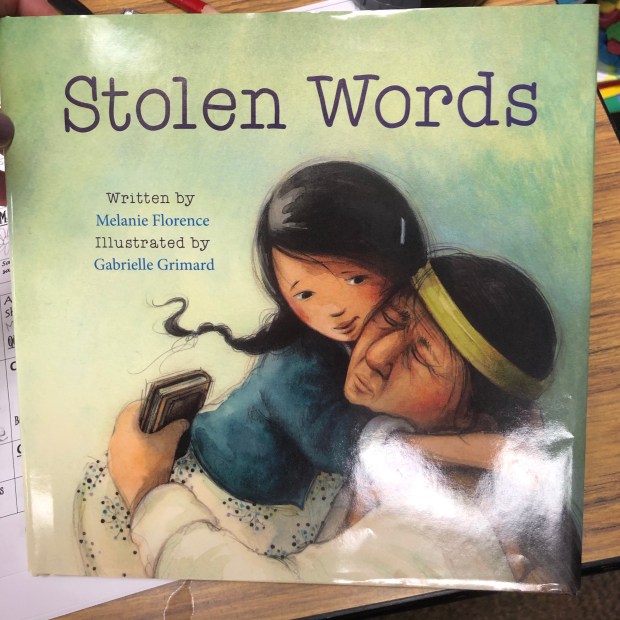

Reading ‘Stolen Words’, a children’s book about a girl who helps her grandfather overcome the fact that he lost his words when he was punished for speaking his own language while at Residential School, really brought home to me the importance of hearing some words in Dakelh each day for everyone, irrespective of our ancestry.

Hearing Dakelh is an important reminder of what the land acknowledgement says: that we ‘live, work and play on the ancestral lands of the Lheidli T’enneh‘. It also instils pride and reinforces a sense of identity for our First Nation pupils.

The Dakelh language and two teenage boys

On one occasion though this sense of pride was mixed with the impression that they were getting away with doing something that they should not be doing, when I overheard two sixteen year old boys talking in what they called ‘their language’.

I had been teaching the boys for a while and knew them quite well, so it seemed like a nice opportunity for me to learn about their culture from them.

They were quite happy to put down their maths work to tell me about how they actually couldn’t say very many words, but that one of their grandmothers only spoke in ‘their language’, having never been forced to learn English.

Next, to my surprise, they voluntarily started teaching me how to say ‘stop doing that’. Which, I admitted, was a pretty useful phrase in my line of work.

So why the furtive glances, giggling and the impression that they were breaking rules before? Surely, these Gen-Z teens know they would never be told off for expressing pride in their identity?

Turns out that before I interrupted them, they had been sat there swearing at each other and sharing some pretty choice phrases in ‘their language’. No wonder the non-rude phrase they remembered from their Elders, and shared with me, was ‘stop doing that’.

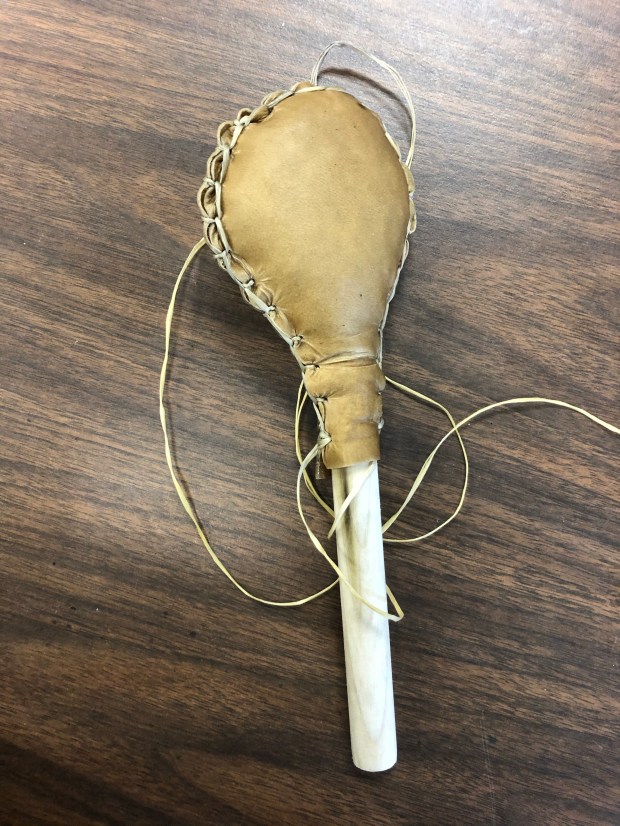

An afternoon making Deer Skin Rattles

“One more question” I said like an over-excited child, “what would they have put inside the rattle instead of the plastic beads we are using?” The Elder, a Métis and Cree woman who had come in to lead the class in a traditional Deer Skin Rattle making activity, seemed a bit taken aback that the ‘sub’ was more eager than the kids, but she smiled and patiently began explaining.

Interestingly, the term ‘Elder’ denotes wisdom not age. ‘Elder’ refers to someone who has acquired great understanding of First Nation, Métis or Inuit culture.

“Usually seeds, but sometimes flint to make the rattles spark when they are used”, was the answer to my question and as she helped the kids sew the deer skin pieces together ready for painting, she taught me all about the importance of rattles and drums in First Nation culture.

I learned that sweetgrass, which she explained is one of the gifts from the creator, is used to bring the rattles and drums to life. By placing them on the instrument before use, they jump and ‘come to life’ when used.

During that afternoon I felt immensely privileged to be able to ask questions and learn from her as the kids happily painted. Particularly as, after she left, the next activity for the kids was some work about the history of rattles which I’d be teaching alone, but thanks to my crash course with the Elder, with confidence.

. . .

Check out Part one…

Part one: First Nation culture in the Canadian classroom

. . .

More about schools and teaching…

A guide to surviving as a British Secondary School Teacher in Canadian Elementary Schools

. . .

That second rattle is amazing 😉

LikeLike